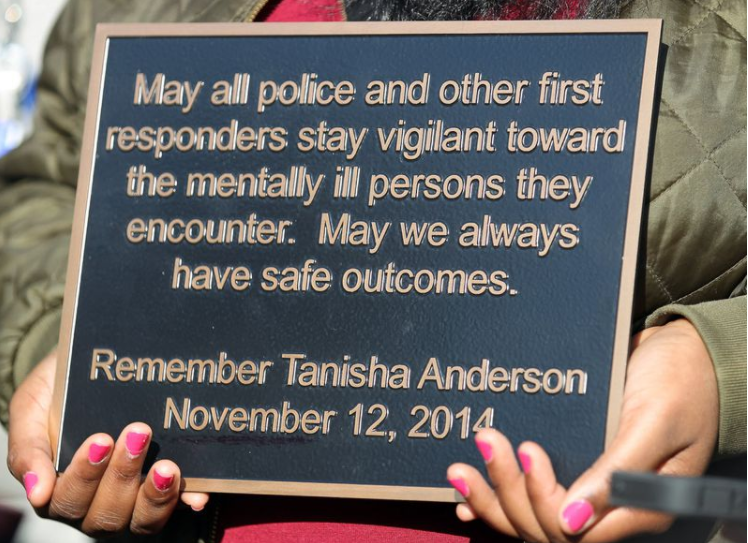

A plaque to remember Tanisha Anderson is displayed Feb. 6, 2017 in front of Cleveland City Hall after the family announced their settlement against the City of Cleveland and two police officers for a total of $2.25 million. On November 12, 2014 Tanisha Anderson was handcuffed behind her back and held on the ground, prone, causing her respiratory problems, ultimately causing her death due to positional asphyxia. Joshua Gunter, Cleveland.com ORG XMIT: CLE1702061223178782 ORG XMIT: CLE1702070308380273 The Plain DealerThe Plain Dealer

CLEVELAND, Ohio – In 1968, 9-1-1 became the emergency lifeline. When there was a health crisis, accident, fire, or crime, you just had to dial three digits, answer the question “911, what’s your emergency?” and help would be on its way.

Now, the help can sometimes make things worse.

For those in mental or behavioral health crises, blaring sirens and uniformed officers can escalate the situation. Being put in a cruiser for transport to an emergency room can push a person over their edge, and what started out as assistance devolves into dangerous restraint, alarming arrest, humiliating handcuffs or worse. Tanisha Anderson comes to mind. In 2014, Anderson’s family called Cleveland police to help her during a mental-health episode. She ended up handcuffed and slammed to the ground, where she died.

More than seven years later, there’s a new voice in town, calling for conversation and policy change and hoping to seize the moment with a new mayor, who says he prioritizes police reform.

A regional coalition called REACH — Responding with Empathy, Action, and Community Healing — is going public TODAY to promote a proven alternative to having police respond to calls for mental health emergencies. The coalition supports what’s known as “care response.” It’s a model that goes a step further than “co-response,” in which police respond to a call accompanied by a healthcare or social worker. Care response instead provides critical health assistance via trained specialists — without a police presence — at what the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration calls Intercept Zero. That’s the first point of engagement during an emergency.

The REACH website offers a detailed explanation of this approach and the way it can protect our residents and help our police force. A key factor is that after the immediate crisis is resolved, wraparound and follow up services are provided, which help people avoid crisis repetition and additional emergency calls.

REACH co-founders, including community advocate Elaine Schleiffer, Josiah Quarles, a housing justice community organizer for Northeast Ohio Coalition for the Homeless, and Lauren Fraley of SURJ NEO, the Cleveland chapter of Showing Up for Racial Justice, have not only rallied a sizeable network, they’ve created a masterful website of clear information and convincing data. They hope to spark conversation, educate people, and influence the policymakers.

Alternative response systems are not new, but Cleveland has yet to fully embrace them. Currently, Cleveland operates a co-response pilot program but only in the police’s Second District. And the primary responsibility for handling crisis incidents on scene falls to members of the department’s specialized Crisis Intervention Team.

Leslie Kouba columnist for cleveland.com and The Plain Dealer. January 14, 2022

Cities including Denver, Portland, and Austin have implemented non-police crisis response programs in which medics, social workers, or mental health specialists — instead of cops — act as first responders. And Quarles says these programs can be instructive, as Cleveland contemplates its own alternative crisis response strategy.

Perhaps most inspiring, Quarles says, is the program called Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets – or CAHOOTS — in Eugene, Oregon. The non-profit White Bird Clinic launched the program in 1989 after organizers asked residents for input through a survey to determine what the community needed in a nonpolice response to mental and behavioral health emergencies. The resulting program relies on “two-person teams consisting of a medic (a nurse, paramedic, or EMT) and a crisis worker who has substantial training and experience in the mental health field.” No one carries a weapon.

How refreshing when leaders ask program receivers what they really need before creating a public service program.

Schleiffer says appropriate emergency response during times of crisis can make a world of difference for families with loved ones with a severe mental illness or addiction issue. Without that expert intervention, those families often try to respond to crises on their own, because they know that when they reach out for help, they will usually get a Cleveland police officer and patrol car.

“For families and individuals most impacted by disruptions in mental and behavioral health, non-police crisis response means the ability to reach out for help when it is truly needed,” she said. “We can save cops, families, and neighborhoods from the frequency of tragedy we currently experience…by implementing non-police crisis response.”

Rosie Palfy, a member of the Mental Health Response Advisory Committee, formed under the federal consent decree to reform policing in Cleveland, is a supporter of REACH.

“More than anything else, I want the stigma of mental and behavioral health challenges to go away,” she says. “A care response will help. No one wants to be seen handcuffed and put in a patrol car when all they need is some compassionate care.”

Indeed. And I wonder when MHRAC’s work will show up in Mayor Justin Bibb’s priorities.

If REACH can be the catalyst for a care response program in Cleveland, Schleiffer, Palfy, Quarles, and many others will have achieved what I see as a much-needed miracle. Until then, Schleiffer says, the best way to access crisis response in Cuyahoga County without an automatic police presence is to contact Frontline Services by calling 216-623-6555 or texting 741741.

Schleiffer says Clevelanders deserve to have that option and better policing overall.

“I want everyone to know that services like emergency detox, suicide response, and other mental/behavioral crises can be responded to without an armed cop presence that escalates the person in crisis,” she said. “I want everyone to know that we all, together, deserve better. … We do deserve better co-response. We do deserve better cop response. And we do deserve a full spectrum of crisis response services, including care response, in which no cops are present.”

I think it’s fair to conclude that had such a response been available in 2014, Tanisha Anderson’s mental health crisis might have ended very differently.

Leslie Kouba, a lifetime resident of Northeast Ohio and mother of four completely grown humans, enjoys writing, laughing, and living in Cleveland with her wife, five cats, and a fat-tailed gecko named Zennis. You can reach her at LeslieKoubaPD@gmail.com.

Test post

Israel's interior ministry says it has deported a Palestinian-French human rights lawyer after accusing him of security threats. Salah Hamouri, 37, was escorted onto a flight to France by police early on Sunday morning, the ministry said. A lifelong resident of...

Salah Hammouri: Israel deports Palestinian lawyer to France

Israel's interior ministry says it has deported a Palestinian-French human rights lawyer after accusing him of security threats. Salah Hamouri, 37, was escorted onto a flight to France by police early on Sunday morning, the ministry said. A lifelong resident of...

Najib Mikati promises justice for Irish UN peacekeeper killed in Lebanon

Lebanon is determined to uncover the circumstances that led to the killing of an Irish UN peacekeeper, caretaker prime minister Najib Mikati said during a visit to the headquarters of the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (Unifil) on Friday. Private Sean Rooney, 23, was...

US appeals court says lawsuit against Lebanese bank can proceed

A US court of appeals has ruled that cases against Lebanese commercial banks can be tried outside Lebanon, paving the way for more cases by depositors seeking to unlock their frozen funds. The court decision, issued on Thursday in a case brought by Lebanese depositors...

2023 Hyundai Elantra Hybrid will surprise you (review)

We are living in the age of cynicism, when everyone seems jaded, as if nothing surprises us anymore. So, when something does deliver more than you’d expect, it’s a genuine delight. Such is the case with 2023 Hyundai Elantra Hybrid Limited compact sedan, starting...

Robert Oppenheimer, father of the atomic bomb, wrongly stripped of security clearance, US says

The Biden administration has reversed a decades-old decision to revoke the security clearance of Robert Oppenheimer, the physicist called the father of the atomic bomb for his leading role in World War II’s Manhattan Project. U.S. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm...

Submit your event

We will be happy to share your events. Please email us the details and pictures at publish@profilenewsohio.com

Address

P.O. Box: 311001 Independance, Ohio, 44131

Call Us

+1 (216) 269 3272

Email Us

Publish@profilenewsohio.com